Preserving the legacy of Bay Area Action’s environmental work from 1990–2000 and beyond.

Learn more...

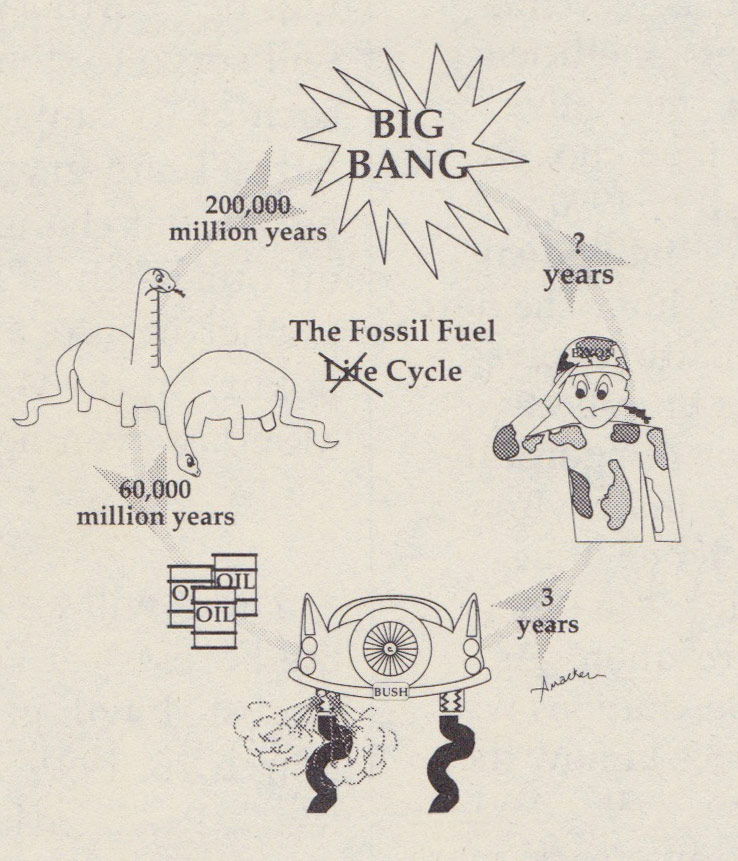

Over 400,000 Americans are facing death in the Persian Gulf. This commitment of so many lives, almost as many as at the height of the Vietnam War, demands a clear, rational, and moral basis for it to be acceptable. Are we there to fight aggression or to fight for Exxon? The answer will vary depending upon who you ask. Regardless of what you believe, one thing is clear: the United States’ thirst for oil has thrown this nation into an increasingly perilous situation, of which the “Persian Gulf Crisis” is merely a symptom. America’s oil problems did not begin when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, and they did not even begin with the Arab Oil Embargo in the 1970s. The problem really began early this century when the oil companies decided for us that petroleum was to be the base of our economy. Oil was not always king. Henry Ford’s original cars, for example, were designed to run on grain alcohol, and electric cars were once far more common than gasoline-powered cars.

It was after World War II that the petroleum industry dramatically expanded its influence into almost every aspect of American life. It transformed agriculture to become almost completely dependent upon oil-based fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides as well as gas-guzzling machinery. In the healthcare sector, pharmaceutical companies stressed synthetic chemical treatments over more traditional (yet highly effective) methods such as sound nutrition and naturally grown medicines. The packaging industry became more and more dependent upon oil-based disposable plastics and used so many different types of plastics that recycling became virtually impossible. Efficient, less polluting public rail transportation systems in Montana, Indiana, Ohio, Oregon, Florida, Alabama, Maryland, Texas, Washington, and California were bought out by “front” companies for GM, Standard Oil of California (Chevron), Firestone, Phillips Petroleum, and Mack Truck — and dismantled to make cities dependent upon automobiles and trucks.

For decades we became more and more dependent upon oil. It was cheap and plentiful, so few really questioned the long-term effects. That all changed in the 1970s when oil prices skyrocketed — all of a sudden, oil was no longer cheap nor plentiful. The first hard data on environmental consequences of oil use also started surfacing. Richard Nixon took steps toward conservation, and Jimmy Carter expanded upon them. Carter created the Department of Energy and promoted significant research efforts toward alternative transportation, renewable fuels, and solar energy. Then Ronald Reagan was elected and the progress made during the 1970s essentially came to a halt. Reagan slashed funding to the programs implemented by Carter and Nixon. The American people had all but forgotten the lessons learned in the 1970s. The consensus among most environmental organizations is that George Bush has continued in Reagan’s footsteps. Now, we again find ourselves in an oil crunch, with the added spice of possibly losing thousands of troops in a war, largely because as a country we have failed to make any significant progress in curing our oil addiction.

Oil use has become so ingrained in our lifestyle that we often fail to see the destructive consequences associated with an oil-based economy. We blame oil spills on oil companies, not on our willingness to use that oil. The smog over most cities is acknowledged as serious health risk, yet we refuse to leave our automobiles. We supported the Shah of Iran for his promises of oil, we supported Hussein in his attempt to disrupt a new Iran, and now we are in Saudi Arabia to fight the “madman” Saddam Hussein and again protect the flow of oil. Environmental destruction: oil spills, air pollution, groundwater pollution, global warming (to name a few) cost us billions every year, perhaps causing disruptions which no amount of money can ever alleviate, but we don’t change our ways. It is estimated that if gasoline prices reflected the true social costs of driving, including environmental degradation, health effects, road building and maintenance, tax losses from paved-over land, and the $300-billion-a-year subsidy the industry is given by the government, gasoline might well cost up to $4.50 per gallon. Thus while the increase in quality of life that an automobile gives us in mobility is perceived as substantial, our auto-centered existence might very well be lowering our standard of living, not to mention that of future generations.

——

By far the largest and perhaps most inefficient use of oil in the United States is for transportation. Since transportation is so decentralized, there is also a great deal individuals can do on their own. Some steps in the proper direction include:

Sources: Greenpeace, Earth Island Journal

——

Published in Action vol 2, no 1 · Jan–Feb 1991